EUROPEAN FLOURS AND THEIR EQUIVALENCE

With the new world we live in, I can no longer review restaurants in Paris. So rather than being idle, I've decided to share my cooking experiences with my readers so when visitors come, or even residents, they will better understand how to translate their cooking with french ingredients.

As with most of us baking has become a hobby. But I had a lot of mishaps, since baking is not my forté. From these mishaps I learned a lot so I thought I'd share them with you.

THIS IS ALL ABOUT FLOUR or in French "FARINE DE BLE"

Since I no longer go out to eat, I thought I’d share with you my cooking findings of experiments that I’ve done while in lock-down.

Although I don't bake bread as much as I used to, because the kilos we're gaining are going straight to our hips, I still bake a small boule for Just Jack maybe once a week.

During my self-imposed quarantine, which I'm still on (I go out maybe once a week), I took the time to learn as much as I could about the different flours in Europe and how they work, with a concentration on French flours.

- The bran – Found on the outer part of the wheat berry

- rich in fiber and minerals

- This is the part that give most flavor to sourdough

- The endosperm – The inner most part of the wheat berry

- rich in starch, and made up mostly of carbohydrates and proteins

- This is the part that is important for gluten development in bread

- The germ – A small part of the wheat berry

- rich in vitamins and healthy fats

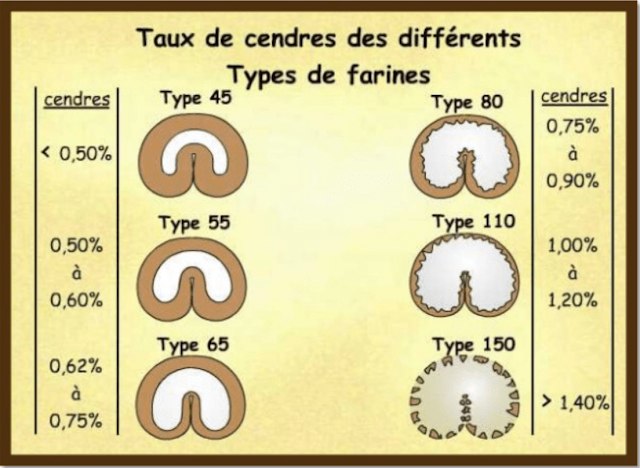

Very simply put, French flours are graded by how much mineral is left in. The lower the number like T45, the less mineral, whereas the higher number, as in T110 the higher the mineral content. But that doesn’t necessarily correspond to protein amount, which I’ll get into later.

I believe American flours are easier to understand, we don’t have as many different flours at the supermarket shelves as we do here in France.

Here's some basic tips I’ve learned along the way.

1. The one factor that I discovered is that the absorbance of water-to-flour is so different than in US flours. Oftentimes, the flours in France absorb more water quicker and faster, so you actually need less water. I can only advise you to use your memory and remember what your dough felt like when you made the same bread in US. So I recommend you use your hands to “feel the dough." I found going with 65% hydration works well with weak flours (below 10% protein), whereas higher hydration for 11% protein flour (78-80%). But, be forewarned, you will very rarely find anything over 12% protein levels in France.

2. There is no “All-purpose flour” per se, nor “bread flour” as in US; they're usually labeled by types of flour, strength, or mineral content. I have friends that mix equal parts T45 with T55 to make an American version of “all purpose flour." There is flour called “tout usage” which does mean "all-purpose" but it’s much weaker than the American version, it’s basically a type T45 with a tad more strength, and only a few brands carry them (Carrefour). It’s my go to for desserts. Hence, when making bread, especially sourdough artisan bread, it's important if you're looking for a "strong white flour" then read the protein level. You could get a T55 which says it's good for bread but the protein level is only at 10% (weak).

3. You’ll see a lot of 00 for pizza dough. And, that’s exactly what it’s used for, pizza. I have used it in place of bread, but it’s not as strong for use with 100% “levain” but works well with commercial yeast, from my experience

4. For grains such as rye, spelt, kasha, teft, bulgar wheat etc., you will not find them at your grocery store. You need to go to the Health-food stores such as Natural.

5. Of course, you can go to the many markets and get flour milled by a farmer. They’re usually sold in bulk, so you’ll need to ask them what the flour is good for.

Well this is about as much as I’ve learned.

Happy Cooking.

Here my favorite sour dough bread recipe to use in France, that I adapted from the “Regular Chef”. I created a checklist for your convenience

INGREDENTS

100 grams levain freshly fed and risen (your own favorite sourdough starter)

325 (for 65% hydration) grams water, tepid (75°F)

400 grams T65 (make sure the protein percentage is at minimum 11%)

100 grams Spelt (épeautre en français)

10 grams fine sea salt

MIXING DOUGH

- [ ] Fill a large bowl with 300g of water at about 85°F (~30°C)

- [ ] Add the entire levain (about 100g) to the bowl and stir to disperse it throughout the liquid.

- [ ] Add 400 g of flour, along with 50g of whole wheat flour (mixture), and stir with a dough whisk or by hand, until all flour is completely saturated.

- [ ] Cover the bowl with a towel or plastic wrap, and allow it to rest in a warm environment (about 85°F or 29°C) for 20-40 minutes.

- [ ] While the dough is resting, mix together 25g of water and 10g of salt in a separate bowl or measuring cup.

- [ ] After 20-40 minutes, add the 25g of water and 10g of salt, and incorporate it into the dough by dimpling and folding it in.

BULK RISE

* Transfer the dough to a clear rectangular container, cover, and return it to your warm environment for 25 minutes.

* During the bulk rise phase, we will perform 5 sets of folds, spaced out at 25 minute intervals.

* After the first 25 minutes, take your dough and perform a set of stretch and folds.

- [ ] One S/F 25 minutes

- [ ] Two S/F 25 minutes

- [ ] Third S/F 25 minutes

- [ ] 4th Coil 25 minutes

- [ ] 5th Coil 25 minutes

- [ ] Cover the container, and return it to your warm environment.

- [ ] If you see any large bubbles on the surface of the dough, pop them so they don’t end up in the final bread.

- [ ] The dough should be soft and airy by now, and it should have grown in size by about 20-30% since the beginning of the bulk rise phase.

- [ ] If it doesn’t seem ready yet, you can return the dough to your warm environment for another 25 minutes and perform another set of coil folds, then proceed from there.

- [ ] After the last set of folds, set the dough aside for about 10 minutes to let it relax.

SHAPE Remove your dough onto a lightly floured work surface, with the top of the dough facing down.

You now have one “floured” side of the dough, and one “unfloured” side.

Lightly flour your hands and bench scraper to prevent the dough from sticking.

Make sure your surface doesn’t have too much excess flour on it, then place down one of your dough pieces with the unfloured side facing down.

Use your bench scraper to form the loaf into a taught ball by scooping it from the side as you rotate it a quarter turn, then scrape it back toward yourself.

Repeat that process a few more times until you feel some tension develop on the outer surface and the dough and it maintains its round shape. Be careful not to over-shape, which can cause the surface to tear.

Again, pop any large bubbles that form on the surface of the dough.

Dust the tops of the loaves with flour, then cover them with a floured kitchen towel and let them rest for about 20-30 minutes

They should flatten, but only slightly if you’ve developed some good tension during the initial shaping. If they spread out too thin, you can give them another round of shaping, as we just did, to develop some more tension.

Then, let them rest for another 20-30 minutes.

FINAL SHAPE- PLACE IN BENNETON OR BOWL LINED WITH A KITCHEN TOWEL SPRINKLED WITH FLOUR OR RICE FLOUR AND REFRIDGERATE FOR 12-24 HOURS (OVERNIGHT)

SCORE, BAKE 20 MINUTES WITH LID AT 500F (250C), LOWER TO 450F (230C) REMOVE TOP BAKE ANOTHER 20 MINUTES

No comments :

Post a Comment